|

| Peasant Children. painting by Vladimir Makovskiy 1890 |

Serfdom in Russia was very much like serfdom in the Polish-Lithuanian

Confederation, but it developed and ended later in Russia than it did in

Poland. Serfs were tied to the land, expected to work a specific number of days

for the landlord and allowed to farm some land for themselves. Serfdom in

Russia, as in Poland, was not connected to feudalism. It developed in both places because the nobility needed a cheap source of labor to work their large estates.

More about serfdom in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

More about serfdom in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Muscovite Russia 1533-1682

Serfdom developed during the Muscovite Period, 1533-1682, on foundations which were laid earlier. The practice was the cornerstone of

Muscovite agriculture and supported the structure of the state. No laws were passed regulating serfs in

the early days, but the government did limit movement of serfs and required that

runaway serfs be returned to the landowner. In 1649 Tsar Alexis issued

an Utoshe, a decree that tied peasants to their landlord’s estates, and

required their labor. The Utoshe confirmed the idea that once a peasant became

a serf, he and his descendants would always be serfs. In Muscovite Russia, the peasant class included serfs,

slaves and state peasants. Peasants could sell themselves into slavery, which

happened during hard times. State peasants worked for the government, not

landlords. As serfdom grew, the

distinctions between serfs and slaves disappeared.

Imperial Russia 1682-1914

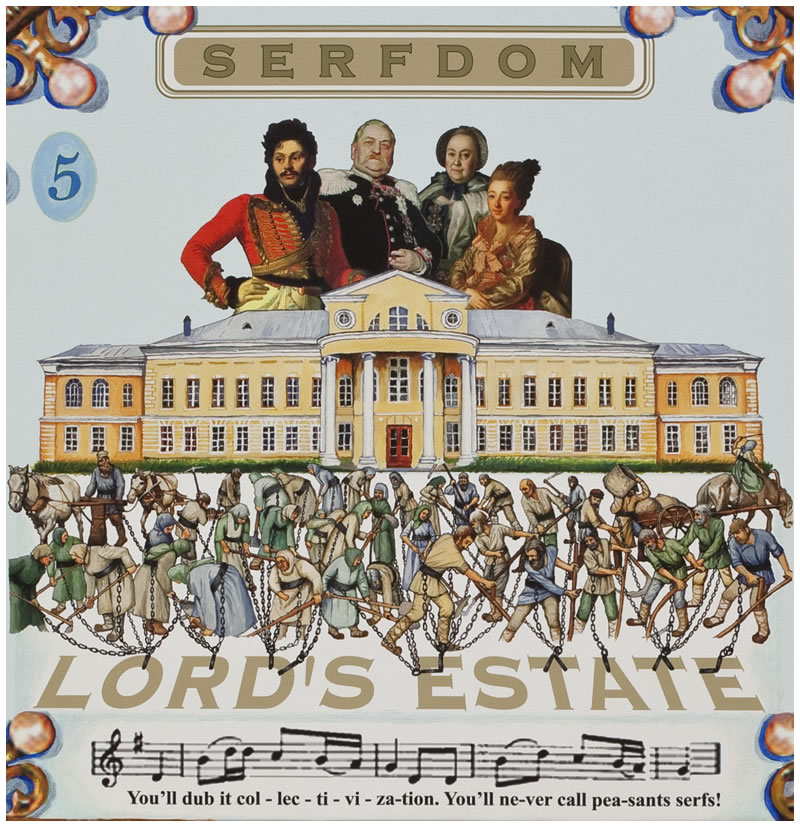

Peter II, The Great, enlarged Russian territory during his rule. He put a tax on the male population,

and made paying it the responsibility of the landlord. However, the landlords passed the

tax on to the serfs. As a result of this tax, landlords began to think of their

serfs as property, which could be bought and sold.

During the rule of Peter’s successors, Catherine I, Anne,

and Elizabeth, serfs were forbidden to buy and sell real estate, mills or

factories. They could borrow money only with their landlord’s permission. In

1736, laws were enacted that required serfs to get their landlord's permission to leave the estate for

temporary employment. In

1754, serfs were listed in the criminal code as property of the landowner. Since

Russian serfs, like serfs in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were attached to the land, when the land was sold, the serfs were

included in the sale. However, in Russia individual serfs could be bought and sold.

Russian territory increased during the rule of Catherine II, The Great. as a result of the Partitions of Poland

(1772-1795), The population

increased by six million people and land by 178,000 sq. miles. Serfdom already

existed in the areas of Poland-Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired by Russia, and Catherine wanted to

expand Russian style serfdom to the new acquired areas. Although Catherine was considered a reformer, her reforms did not improve conditions for the serfs. In 1775, when she reformed

local government, the serfs were overlooked. Rights of the landlords were strengthened and they were acknowledged

as the full owners of their estates without any restrictions. She gave huge

grants of state land and peasants to her supporters and favorites. Serfs were

forbidden to leave estates and to remain in their place and calling. In the

Census of 1794-6, 53% of all peasants and 49% of Russia’s population were

serfs.

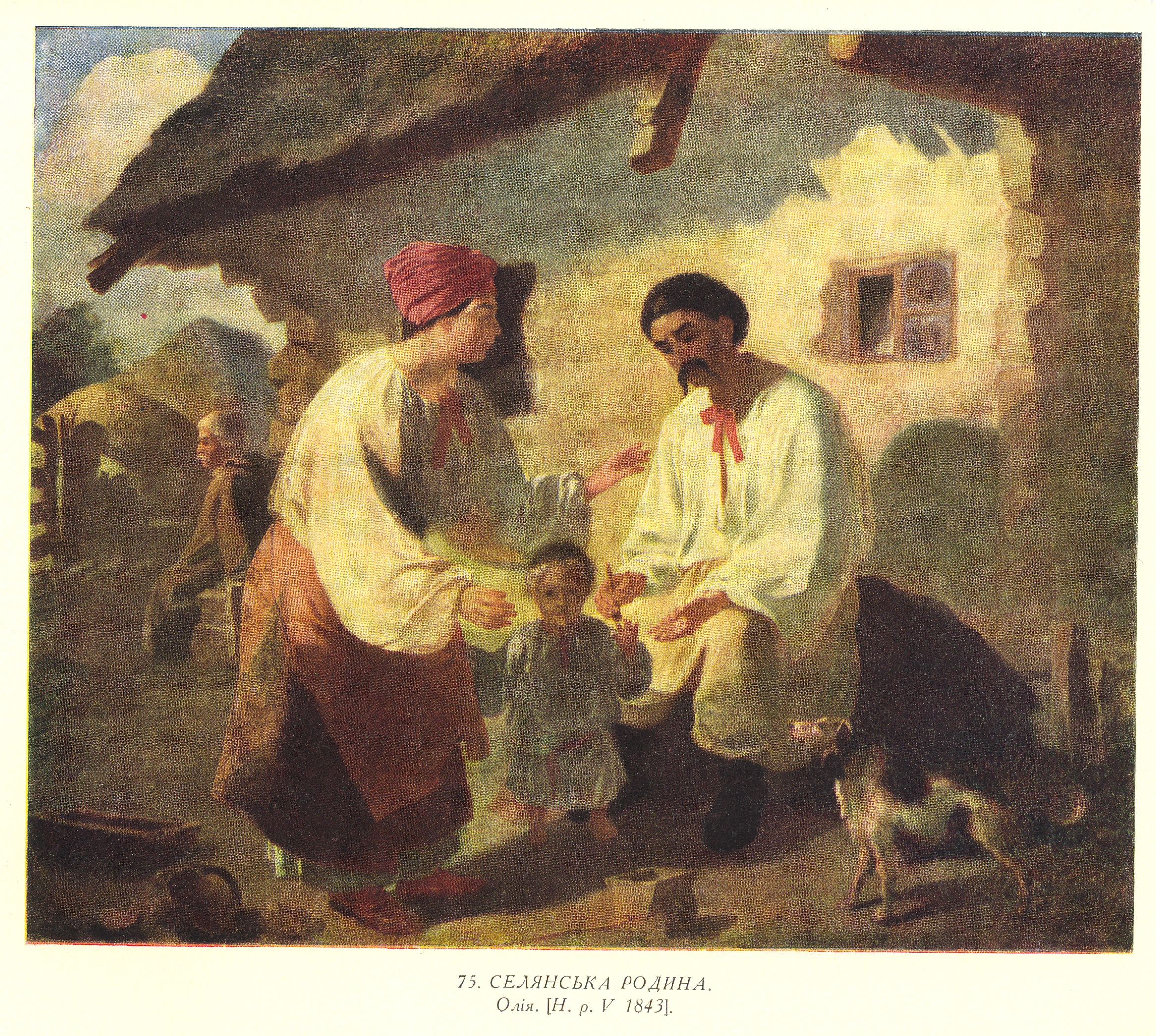

Russian serfs owned and farmed their own plots, which were

larger than the plots of serfs in the Austrian Empire. They could also sell their surplus

crops for a profit. If they paid a fee, the “Obrok”, to their landlord, they were allowed to leave the estate to work elsewhere for

wages. By 1857, 67% of serfs were

on the “Obrok.”, which became a source of income for the landlord. One half of Russian peasants were

state serfs who paid a tax to the state and were allowed to leave the

community to find work. They generally were better off than peasants who were privately owned. Landlords could take serfs from the land and use them has servants in their house. House serfs did not work the land and had no plots of land for themselves.

It was possible for serfs to become wealthy, but this was not common. Western European travelers in Russia during the 19th century noticed that Russian peasants appeared to be better off than peasants in France or Ireland, had larger houses, more farm animals and larger plots. Though some Russian serfs were more prosperous than peasants in other areas of Europe, they lacked rights enjoyed by peasants in most other European countries. They had no civil rights and no way to address wrongs inflicted on them by their landowner. They could not leave the landlord's estate without his permission. They could be exiled to Siberia for bad behavior. Some had to get the lord's permission to marry. They could be bought and sold. Their lives were totally subject to the will of their owner.

|

| Peasant Children. Photograph by William Carrick, 1860 |

It was possible for serfs to become wealthy, but this was not common. Western European travelers in Russia during the 19th century noticed that Russian peasants appeared to be better off than peasants in France or Ireland, had larger houses, more farm animals and larger plots. Though some Russian serfs were more prosperous than peasants in other areas of Europe, they lacked rights enjoyed by peasants in most other European countries. They had no civil rights and no way to address wrongs inflicted on them by their landowner. They could not leave the landlord's estate without his permission. They could be exiled to Siberia for bad behavior. Some had to get the lord's permission to marry. They could be bought and sold. Their lives were totally subject to the will of their owner.

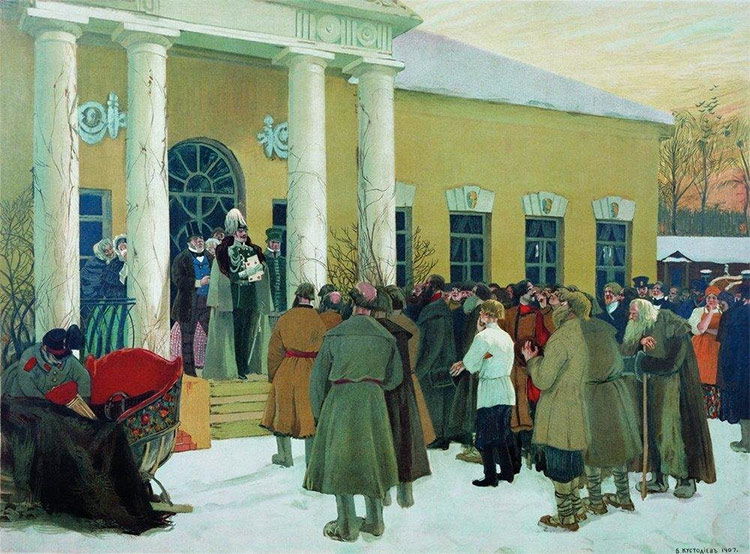

Serfdom Ends in Russia

Attitudes toward serfdom began to change during the 19th

century. Many Russians believed that serfdom was inhumane and should be done

away with. The Crimean War showed

that there problems in Russian

society and changes were necessary. In 1856, Tsar Alexander

II said “Better to abolish serfdom from above than wait until it abolishes

itself from below.” When he came to the throne in 1858, 37% of all Russians

were serfs.

|

| "Reading the Manifesto." painting by Boris Kustodiev, 1907 |

|

| Tsar Alexander II |

The serf was now free and owned his land. The provisions of the emancipation were designed to protect the interests of the landlords as well as those of the peasants. The landlord retained about half of estate’s land, the peasants received the other half. The average size of peasant plots was about 27 acres in the Russian Empire, 18 acres in the parts of Ukraine, which were acquired in the Partitions of Poland. The landlords were compensated by the sale of government treasury bonds, which were to be paid for by the former serfs over a period of 49 years. The former serfs continued to pay the head tax, even though it was no longer paid by other Russians.

|

| "Harvesting" painting by G. Myasoyedov 1887 |

The emancipation benefited the landlords more

than the peasants. Serfs received land, but not enough. Their new land

allotment was 10% to 40% smaller than what they had before emancipation, depending on where in

Russia they lived. In most areas, the land was given to the village commune (Mir), not to individual peasants. The Mir divided the land and paid the taxes.

Peasants were free, but still had restrictions on their movement. They were

still tied to their communes, they were judged by customary law. Only serfs who worked the land received

land, household serfs got nothing. State peasants received larger land grants and fared better than peasants on the land

of private owners.

Peasants in Ukraine, which came to Russia in the Polish Partitions, did

not have a tradition of communes, the land was owned by individuals, so they continued to own their own plots.

|

| Peasant Girls. photo by Prokudin-Gorsky, Library of Congress. |

Emancipation was a compromise, serfs had freedom, but not

full equality. They had land, but

not enough. Many were dependent on their former landlords.

Unlike the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, where free public education was provided for former serfs, no provisions were made their education in Russia. Unable to better themselves in Russia, many chose to leave and immigrate to the United States, Canada and the countries of South America.

Sources:

The Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, www.encyclopediaofukraine.com

Conquest, Robert, The Harvest of Sorrrow, New York, 1986.

Pipes, Richard, Russia Under the Old Regime, New York, 1974.

Plokhy, Serhii, The Gates of Europe, New York, 2015.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas, A History of Russia, New York, 1963.

Subtelny, Orest, Ukraine, A History, Toronto, 1988.

Sources:

The Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, www.encyclopediaofukraine.com

Conquest, Robert, The Harvest of Sorrrow, New York, 1986.

Pipes, Richard, Russia Under the Old Regime, New York, 1974.

Plokhy, Serhii, The Gates of Europe, New York, 2015.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas, A History of Russia, New York, 1963.

Subtelny, Orest, Ukraine, A History, Toronto, 1988.