Just outside the city of Ternopil’ is the village of

Bila. It was a farming village,

about 3 km walk to the center of the city. Most of the people of this village made their living from

farming, but since their plots were small, many of them have to work at other

jobs to help make ends meet.

Ukrainian newspapers had advertisements for jobs in

America. They promised plenty of

land, enough food and drink for everybody. There were jobs in the coalmines of Pennsylvania, and in the

steel mills in Ohio and in factories in New England. There were ads for farms in North Dakota, showing palm trees

and lots of land. Life was hard in

Galicia, a part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, the whole family worked very

hard and made very little. Why not go to America, work, for a few years and

them come back to Bila, and live like a rich man? So in 1907, Sylvester Rychlyj

decided to leave his wife and seven children and go to Tower City, Pennsylvania

to work. He traveled with another

man from his village, Wasyl Boyko.

When he got there, he found work as a farm laborer. It didn’t take him long to realize that

life was better in America, and he decided that instead of returning to Bila,

he would work to earn enough money to bring his wife and family to live in the

United States.

So, what was he leaving behind? What was it like to live in

a farming village in Galicia? Why

did so many people leave, and never return? This is the story of my great-grandparents, Sylvester

Rychlyj and Marya Bryniak Rychlyj, who were born in Bila. It was told by my great aunt, Katherine

Rychly Pylatuik, to her daughter Julia Lawryk, in 1988.

When Sylvester married Marya Bryniak in 1895, they moved

into a one- room house with his parents and brothers and sisters. It took him ten years to save enough

money to buy a house for his family.

The house was built of wood covered with clay, with a straw roof. It was old, and painted white like the

other houses in the village. The

location was good, only a block away from the well. There was a “pryspa” around the outside of the house,

a sloping ledge, in order to carry rainwater away. Sometimes the pryspa was used as a bench, but it

really wasn’t comfortable. In

front of the house were some fir trees and an ash tree. In back of the house were raspberry

bushes and cherry trees. Around

the house was a wooden fence. All

the houses had numbers, from 1 to 350, and mail was delivered directly to the

house.

|

| Man sitting on a "prypsa" |

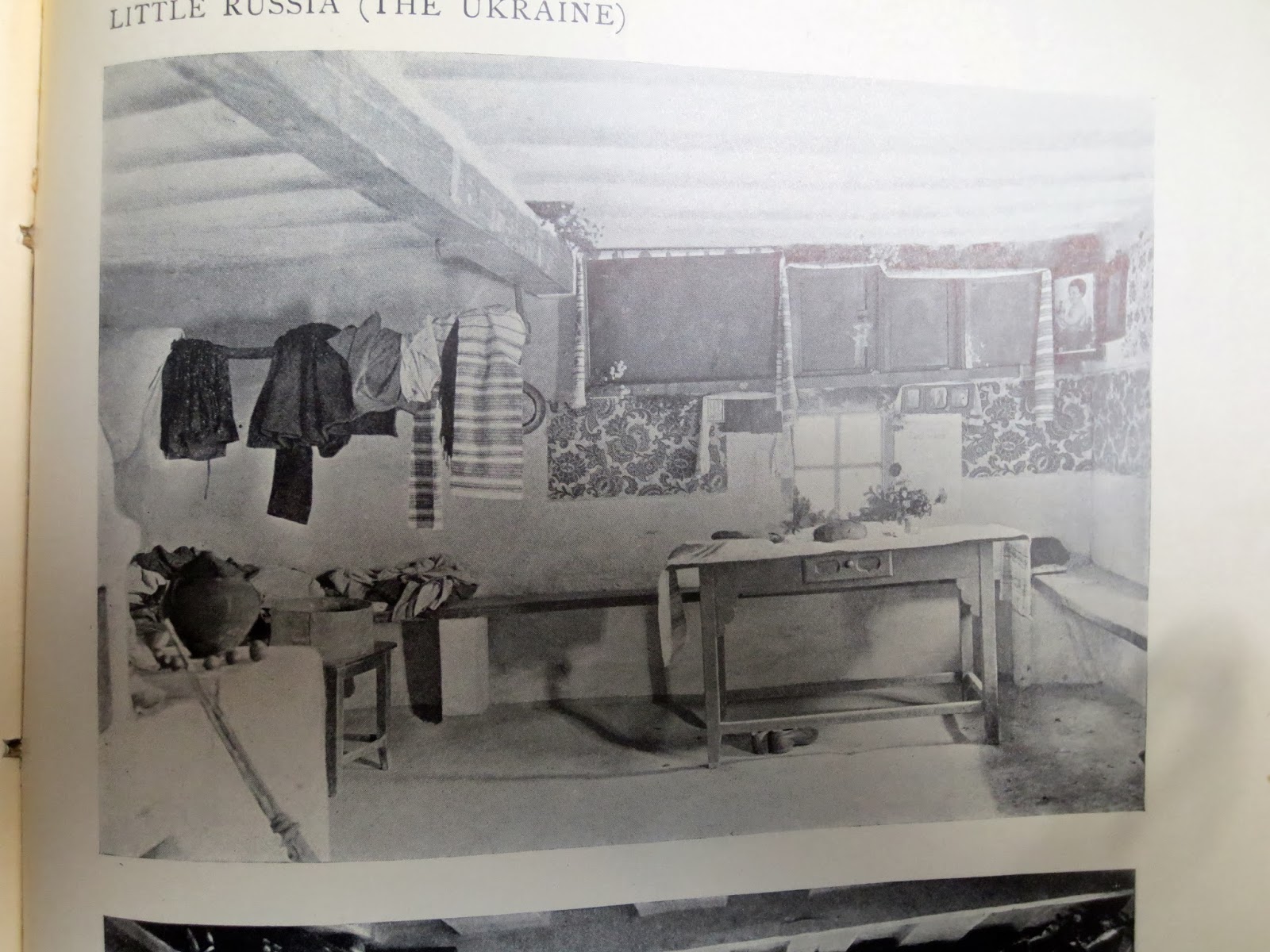

Inside the house, there was one room, painted white with the same material

used on the exterior, which served as a living room, dining room, kitchen and

bedroom. In one corner, there was

a stove and bread oven, made from bricks. Pots and pans were stored in the

stove. There was a storage room next to the kitchen area. In another corner was

a table with benches along the wall.

The table was a large wooden box, the top could be lifted and inside was

a storage area, where clean clothes and linens were kept. Just before he left for America,

Sylvester built a small table and benches for the children. There was one bed, which had a mattress

filled with straw, that was changed every month. On top of the mattress there was a sheet and a feather

quilt. Colorful embroidered

pillows were laid on top of the quilt. On the walls next to the bed were hung

with mats made of woven plant material to keep out the damp.

The thatched roof sagged in places, it was so low that a

child could touch it easily. The

wooden rafters were used to hang braided strings of onions and garlic as well as

dried corn and dill. Dirty clothes

were thrown on the rafters until they were washed. The floor of the house was hard packed dirt. There was no bathroom or outhouse,

everyone just went outside.

|

| Painting of the interior of a Ukrainian house in Eastern Ukraine. The bread oven is next to the stove. |

So, where did the seven children sleep? Marya slept in the bed, along with the

youngest child. If a child was

sick, he or she slept with Marya.

Two children, usually the younger ones slept on the stove. The older

ones slept on the benches. During

World I, soldiers from the various invading armies were billeted in village

houses. As many as five soldiers

slept on the floor. along with the family of nine people.

The Rychlyj family was poor, they had one cow, chickens,

ducks and a dog. They bought next

to nothing—scarves for the girls, shoes and boots, and some items of clothing

that could not be made at home.

They grew the food they ate, including the grain used for bread. They rarely ate meat—and when they did

it was chicken or fish. Meat and

white bread were special foods, eaten only on holidays. They bought salt, soap

matches, naptha, and baking powder at a village store. Most of the village

stores were owned by Jews. There

were two butcher shops that owned by Ukrainians, but the Rychlyj’s rarely

bought meat, and when did they did, they went to Ternopil’, where things were

cheaper. My grandmother told me that the first time she ate beef was in the

United States. There was a “root

cellar”, an underground food storage area, outside the house, which Sylvester

built it shortly before he left for America. The walls were covered with stones, there were stone steps

and a door that locked. Theft of

food, and other things, was a problem in the village. Once before Easter, the family’s holiday foods were

stolen. Someone cut a hole in the

wall of the house, and took the food.

This happened while the family was inside the house, sleeping. The thieves must have been very

careful, because nobody woke up, and the theft wasn’t discovered until morning.

The family owned a Bible, written in Ukrainian, church

prayer books, which were written Church Slavonic, school books in both

Ukrainian and Polish (both languages were taught in the village school). The children also had a few school

supplies, which they kept in small wooden boxes. Their toys were homemade, the girls had cornhusk dolls, and balls

made from cow hair. The family also owned a sled for wintertime fun. They had playing cards, which provided

wintertime entertainment for the family.

Life in the village was hard, but many of the other

residents of the village were relatives, so visiting family was a favorite

pastime of my great-grandmother.

Her mother and brother lives nearby and there were many cousins and

other family close as well. My grandmother

left Bila in June of 1914,

just before World War I began.

After that, village life was never the same.

A note about the photographs: The only photographs I have found of houses in Ukraine around the turn of the last century are of places in Eastern Ukraine, which was part of Russia at that time.

Sources: Kateryna (Kashka): Autobiography by

Katherine Pylatuik Lymar, as told to her Daughter, Julie in 1988. By Julia

Pylatuik Lawryk, copyright 1988.

Picture sources: Ukrainian Arts, ed. Anne Mitz, New

York, 1955.

L’Arte Rustique En Russie, Edition Du “Studio”, Paris, 1912.

No comments:

Post a Comment