| A wedding in Western Ukraine about 1918. |

Weddings in the village of Bila, just outside of the city of

Ternopil’, Ukraine, were as important 100 years ago as they are in the United

States today. Since the villagers

rarely traveled far from their home, and didn’t have television, radio, movies,

or sports to watch or participate in, events such as weddings and baptisms and

religious holidays were major

events.

events.

| The village of Bila is just east of the city of Ternopil' |

| Groom coming to the Bride's home with a "Tree of Life" and a group of musicians, |

A Ukrainian wedding in the old country had traditions that were followed very carefully. A couple wasn’t considered truly married until all the required customs were performed. Although the wedding was a religious event, many of the customs came from older folk beliefs, some of which had pre-Christan roots.

My great aunt, Katherine “Kashka” Pylatiuk, witnessed many

weddings in the village of Bila, and tells about them in her autobiography. I am going to add information about

Ukrainian weddings with Katherine’s first hand story.

Although many weddings in traditional cultures were

arranged, young women in Ukraine had more say in the choice of a spouse than

most. I have read that the Ukrainian woman chooses her own spouse—she has the

last word in making the marriage decision. It was also possible for a woman to propose to a man. When a man wanted to propose to a

woman, he sent several friends to propose a match to the woman’s parents. The

daughter was present in the house, standing in a certain place. If she

accepted, she would give them embroidered linens, called rushnyky, which they

would put over their shoulders like a scarf. If she refused, she would hand them a pumpkin. An saying developed from this custom: “to

give someone a pumpkin” came to mean “to refuse to do something”.

Sunday was the day when most weddings took place. Several events took place on the days

leading up to the wedding. On Friday,

the wedding bread, the “korovay” was baked. This was special bread, made with wheat flour and eggs, with

three layers, with elaborate decorations made of bread dough.

| Ukrainian wedding bread, this one has only two layers. |

When she was 13, Katherine served as a bridesmaid for a

neighbor. On Saturday, the day before the wedding, she went to

the bride’s house and helped make wedding crowns from the periwinkle vine,

which would be used in the wedding ceremony. The bride’s hair was braided with flowers and ribbons. Then the bride and the bridesmaids went to

the houses in the village and invited friends and family to come to the

wedding.

| In this painting by Fedir Krychevsky, "The Bride", the bridesmaids help the bride dress for her wedding |

On Sunday, the bridegroom went to the bride’s house, and

then the wedding party proceeded to the church. As he left his house, the groom’s mother blessed him and threw

either grain or coins over him.

Sometimes the bride and groom rode to the church in a wagon, in some

areas they rode on horseback, and in other areas they walked. The whole family, the guests and the

musicians followed the couple. The

priest met the couple at the door of the church, and the wedding ceremony began

there. The bride and groom walked down the aisle together. An older male friend served as the “starets”, and a female relative served as the “staretsina”

and each held an icon during the ceremony. There were asked to do this because they would provide good and examples and advice for the newly married couple. The best man and the maid of honor held

the periwinkle crowns over the bride and groom’s heads during most of the

ceremony. Other members of the wedding party held candles. During the ceremony,

the couples’ hands were tied together with a rushnyk, (embroidered towel), and

the priest led them around a small altar three times.

|

| Wedding bread on an embroidered rushnyk and periwinkle wedding crowns |

| Painting by Nickolai Pimonenko, 1908. "Wedding in Ukraine" |

After the ceremony, the wedding party and guests went to the

bride’s home for a celebration. My

great-grandfather, Slyvester Rychlyj, was a musician, playing either the cymbaly

(hammered dulcimer) or the violin, and played often for village weddings. The band was made up of a bass, a

cymbaly and a violin. Their

payment for playing at the wedding was the bottom layer of the wedding bread,

which Sylvester and his family considered a real treat.

Food and drink were served, “vareneky” (pirogi), bread and

borscht (beet soup) with meat, if the family could afford it. There was plenty

of beer, in fact, when she was 11, Katherine participated in her uncle’s

wedding by serving beer, before this she could only watch the festivities.

As gifts were presented to the couple, each guest sang a song that was “just right” for the couple, these songs were often teasing or bawdy. My grandmother, Pauline Rychlyj, told me about some of these songs, and from what she said, there were often bawdy. Katherine told about her Uncle Oleksa’s wedding, where her mother sang a song for her brother-in-law that was not very flattering. The bridal couple was upset, but she didn’t stop singing since the guests loved her song. As each gift was presented, the presenter was given a piece of the wedding bread.

Music and dancing continued for most of the night. Unlike today when people dance as couples, most of the dancing was circle dancing. My grandmother mentioned that she was always surprised by how loud a three-piece band could play. Near the end of the celebration, the bride’s hair was unbraided, and in some areas of Ukraine, cut short. In the village of Bila, a wooden hoop was put on the bride’s head, and her hair was covered with a kerchief, the sign of a married woman.

As gifts were presented to the couple, each guest sang a song that was “just right” for the couple, these songs were often teasing or bawdy. My grandmother, Pauline Rychlyj, told me about some of these songs, and from what she said, there were often bawdy. Katherine told about her Uncle Oleksa’s wedding, where her mother sang a song for her brother-in-law that was not very flattering. The bridal couple was upset, but she didn’t stop singing since the guests loved her song. As each gift was presented, the presenter was given a piece of the wedding bread.

Music and dancing continued for most of the night. Unlike today when people dance as couples, most of the dancing was circle dancing. My grandmother mentioned that she was always surprised by how loud a three-piece band could play. Near the end of the celebration, the bride’s hair was unbraided, and in some areas of Ukraine, cut short. In the village of Bila, a wooden hoop was put on the bride’s head, and her hair was covered with a kerchief, the sign of a married woman.

| A Ukrainian woman covered her hair with a kerchief after she was married |

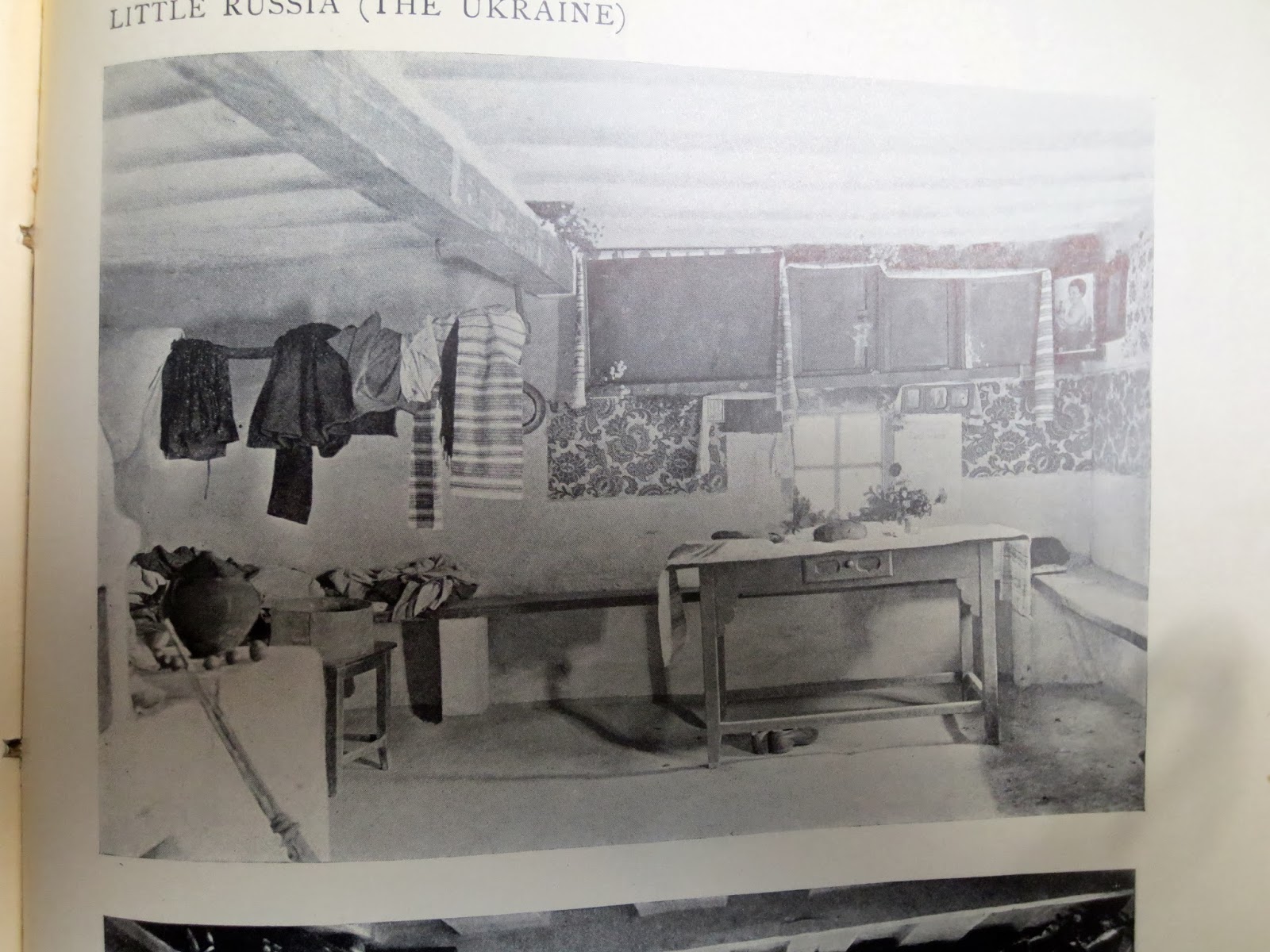

Since most people in the village lived in one or two room

houses, you may wonder how the couple could spent their wedding night in private, since

were no hotels in the village, and no one could afford to go to a hotel in

Ternopil’. Every house in the village had a

storeroom for foodstuffs, this

room was cleared out and decorated, a bed brought in and icons were hung over

the bed.

After the newly married pair retired to the “kormora”

(nuptial chamber/ storeroom), the rest of the guests continued to celebrate

into the early hours of the morning.

To the wedding guests, Monday morning arrived too soon. It was a work-day, and nobody

could ever miss work.

| ||||

| Katherine Rychlyj and Oleksa Pylatiuk on their wedding day in Minneapolis MN, 1923. Their wedding took place on a Sunday, according to Ukrainian tradition. |

SOURCES: Katherine (Kashka), Autobiography by Katherine Pylatiuk Lymar as told to her daughter, Julie in 1988. Copyright 1988.

Tetyana Poshyvalo, "Rituals and Traditions of the Ukrainian Wedding", WUMag, www.wumag.kiev.ua

"Wedding Traditions in Ukraine, Wedding Day Phase". virtual-museum.sunsite.ualberta.ca

|