|

| Ukrainian school in 1938. Photo by Margaret Bourke White, collection of MOMA. |

Many people assume that the great wave of immigrants arrived

in the United States from Eastern Europe were uneducated, illiterate people,

suited only for manual labor.

However, I have found that my extended family, although they were very

poor, coming from eastern Galicia, the poorest part of the Austria-Hungarian

Empire, or from northern Poland, ruled by Russia, or from Russia itself, were

surprisingly well educated.

There was a school in the little village of Bila, which just

outside the walls of the city of Ternopil’ home of my grandmother’s family. My great Aunt, Katherine Rychly described the school where she developed her life-long love of reading in her in her autobiography. The school wasn’t far from the family home, and was

attended by boys and girls, the children were taught by both men and women.

She didn’t mention if the boys and girls attended classes together. The first and second grade children

attended for a half-day, and from third grade on, the children attended a full

day of school. There was a separate class for each grade.

From the education

levels stated in the 1940 US census, the highest grade completed by a Rychly

family member was 7th grade, so I am assuming that the school went

through the 8th grade. Instruction was in both the Polish and

Ukrainian languages. Katherine

mentions that the textbooks were in both languages. In 1890, an agreement was

made between the Poles and Ruthenians (an old name for Ukrainians in Austria),

in Galicia that allowed partial Ukrainianization of the school system and the

inclusion of Ukrainian culture in the school curriculum.

Every two weeks, the children had

religious education, provided by the church. The Polish children received their education from the Roman

Catholic priest, the Ukrainian children were taught by a Greek Catholic

priest. In addition to the regular

subjects, the girls were taught needlework and crocheting.

My Aunt’s formal

education ended after the third grade, in 1914, when World War began on August,

1914. There was no more school in the village of Bila, since Ternopil’ was

invaded by various armies for the next four years. After the war, Eastern

Galicia became part of Poland, and Katherine was too old for school, and was

working to help support the family.

In the village, there was a building that served as a

community center, which was also used for evening discussion groups, called

“readings,” which were closed to women. There the more educated men shared

their knowledge with the less educated men of the village.

I made an informal survey of my extended family’s education,

using data from the 1940 US Census, which noted the highest grade of education

completed by each person listed. I

also checked the 1930 US Census, which recorded whether the person could read

and write.

The Rychly, Koshuba and Nyznyk families immigrated from Galicia,

part of the Austria-Hungarian Empire. In the Rychly family, the highest grade

completed was 7th grade, the lowest was 3rd grade. All the Rychly family members who immigrated to the United States

could read and write when they came here. It is interesting to note that most children in the

United States completed only four to five years of school during the early

years of the 20th century. In the Koshuba

family, the highest grade level

completed was 8th grade, the lowest was 6th grade. My paternal grandfather John Nyznyk

completed 5th grade, but my grandmother, his wife, was illiterate.

|

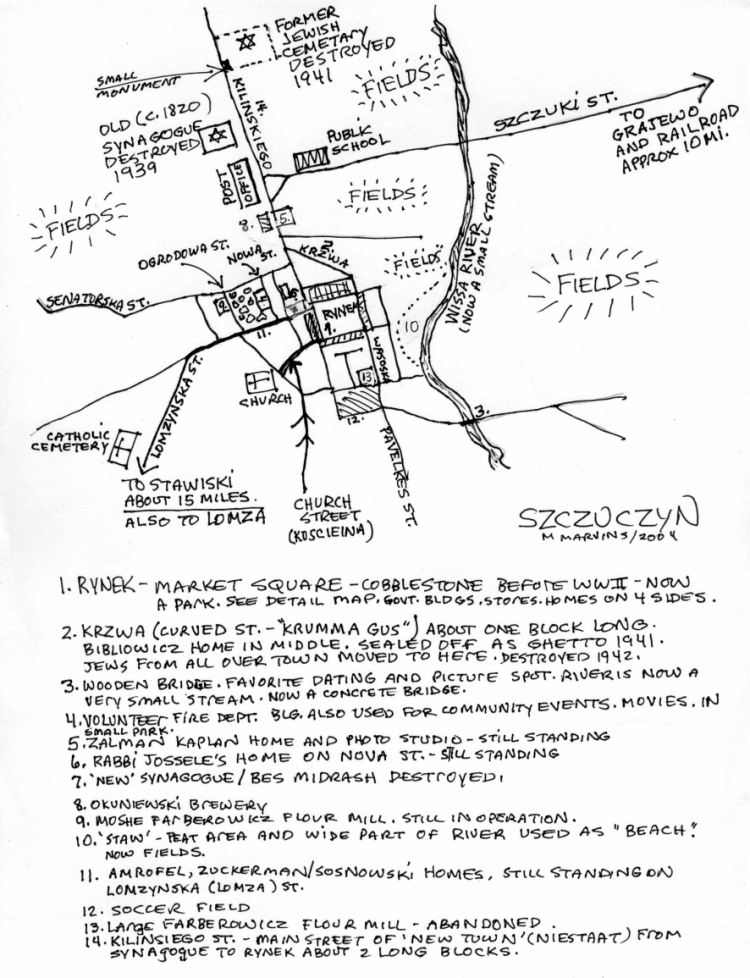

| Map of Szczuczyn, showing the location of the Synagogues and Public School. Source: Jose Gutstein |

On my husband’s side of the family, the Krause

(Karbovsky) and Markin (Monkovski)

families lived in Northern Poland, which was part of the Russian Empire at the

time of their immigration. In Sczcuczyn, ancestral home of the Krause (Karbovsky) family, Jews attended the public schools as well as religious schools.

The Gerstein family lived in Russia. I do not have any information about the kind of public education they received in their villages, although all Jewish men received a basic education in religious schools. Berdichev, original home of the Gerstein family was known as a center of Jewish learning and had a famous Yeshiva located here. My husband's paternal grandfather, Morris Gerstein, was listed in the 1940 US census as having no education, yet he did know how to read and write.

The Gerstein family lived in Russia. I do not have any information about the kind of public education they received in their villages, although all Jewish men received a basic education in religious schools. Berdichev, original home of the Gerstein family was known as a center of Jewish learning and had a famous Yeshiva located here. My husband's paternal grandfather, Morris Gerstein, was listed in the 1940 US census as having no education, yet he did know how to read and write.

There appears to be a big difference between the amount of education

that the men and women received in the Russian ruled areas, although religious education was available to women. In the Krause

family, all the men who came to the United States had an 8th grade

education. I have no information about the education of the men who immigrated in the Monkovski family,

since I have not found them in the 1940 US census. The Monkovski women’s

education varied, the lowest was 2nd grade, the highest was 6th

grade.