|

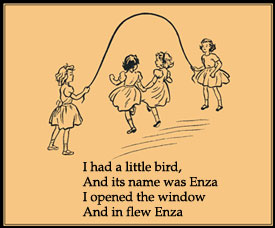

This rhyme was popular in 1918 |

When I first posted this article in 2014, I thought that pandemics were something in history books, the advances in medicine guaranteed that pandemics were something that would never happen again in the United States.

Only six years later, we are in the middle of another pandemic, caused not by the influenza virus, but by Covid 19, a virus from the same family as the common cold. Much to my surprise, history seems to be repeating itself. There is no cure available, the only thing that people can do to prevent contracting the very contagious virus is to isolate themselves and try to avoid contact with infected people and those who may be carriers of the virus. Governments responded in the same way as they did 100 years ago, closed schools, businesses, entertainment venues and told people to isolate themselves in their homes. Like today, the disease is lethal and there is no treatment. Most people survive the virus, but many people succumb to it and die.

There are similarities between the 1918 Pandemic and the Covid 19 Pandemic. Many people believed that the virus started in China. People in 1918 looked for cures, none of which were effective. People were asked to self isolate and wear masks in public. There was a shortage of doctors and nurses, and people to handle the resulting deaths and burials. In 1918, people got tired of self isolation and in the summer of 1918, decided not to stay at home in isolation. The result of this was a second and more lethal wave of the flu in the fall. It is ironic that looking back 102 years to see how the 1918 flu was contained resulted in people using many of the same measures.

One hundred and two years ago,

in 1918, the United States faced a pandemic so lethal that 195,000 people died

from it just during the month of October. At the time it was called the Spanish

Flu, but it didn’t originate in Spain.

It was a quick killer, hitting young adults, many dying within a day or

two after showing symptoms. Nobody

knows how many people died of the flu in 1918-1919, but it is estimated that as

many as one-third of the world’s population at the time was infected, and as

many as 50 million died, more than three times the number of deaths in World

War One. It is believed that more people died in a year from the flu pandemic than

the bubonic plague, the Black Death of the Middle Ages, killed in a century. When

the Flu Pandemic ended in 1919, 28% of the American population had been

infected and between 500,000 and 675,000 people died.

It reached its height

in October of 1918, just before the end of World War I. The War, with its

concentration of troops probably helped its spread and made it a

pandemic. It was deadly, killed quickly, sometimes within hours.

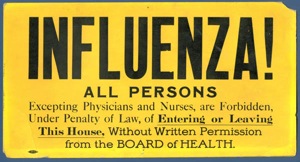

Schools, theaters and other public places in the United States were closed to

keep the flu from spreading. Deaths were so numerous, that funeral homes

and cemeteries couldn't handle the numbers. People were buried in mass graves,

and the size of funerals were limited and often held outdoors in order to

curtail the spread of the disease. There was no treatment, quarantine was about the

only preventative measure that was effective.

There are several

theories about the origin of the Flu in 1918, one points to the town of Etaples

in France, which was a major troop staging area, and the location of a military

hospital. Other theories point to

the East, specifically China, which experienced an outbreak of respiratory

illness in November 1917, which was identical to Spanish flu. How did the flu get from China to

Europe? China wasn’t involved in

World War One, but the link may have been Chinese workers brought to the Western

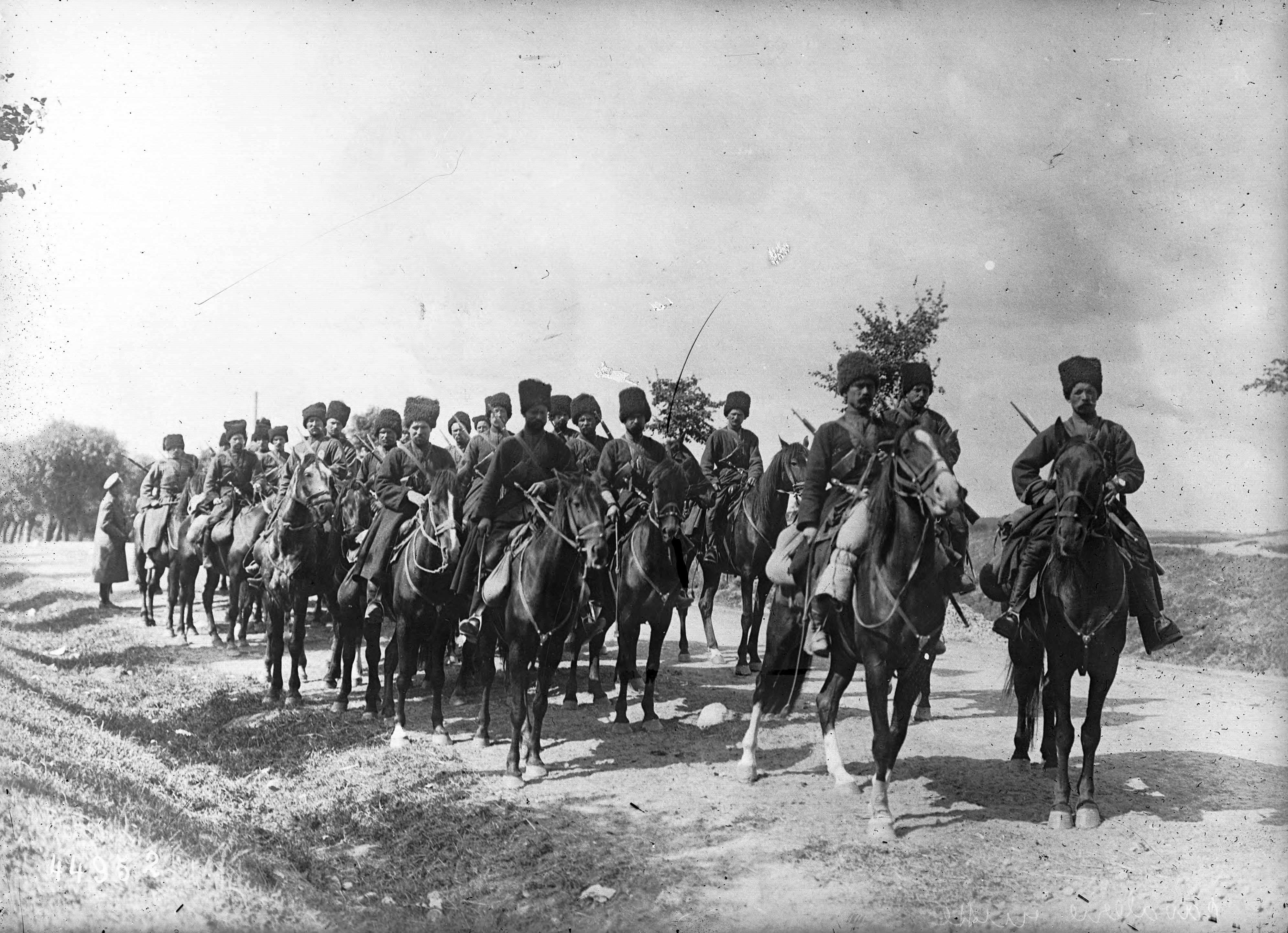

Front, in Europe, to labor behind the front lines. Travel, now worldwide due to the war, helped the flu virus

spread from Europe to the rest of the world. Soldiers in close quarters were easily infected due to

physical proximity, weakened immune systems because of poor nutrition, exposure

to chemical weapons, and stress.

There were three

waves of flu in 1918. The first,

which hit in the spring and early summer, was mild, and most of the people who

contracted it survived. In the United States, it was first reported in Haskell

County, Kansas, in early January 1918.

By March 11, it had spread to Queens, New York. People who were sickened by flu in the first

wave were lucky, since they recovered from the flu, they developed immunity to the virus. A second more dangerous strain appeared

in August 1918, in three places at almost the same time: Brest, France,

Freetown, Sierra Leone in West Africa, and Boston Massachusetts. Between January and August, the virus

had mutated and became deadly. The third wave continued through the spring of

1919.

|

| This map views the earth from the top--the North Pole, showing the spread of the virus from China to the rest of the world. |

In May 1918, young

soldiers in Europe came down with the flu, most recovered, but some developed a

virulent form of pneumonia. Within

two months, the flu spread from the military to the civilian populations of

European cities. It continued its

spread into Asia, Africa, and South America and back to North America.

During the last week

of August, dockworkers in Boston, Massachusetts developed flu symptoms of high

fevers, severe muscle and joint pain.

Between five and ten percent of the men with flu developed

pneumonia. The flu spread

quickly to the city of Boston. By

mid-September it had spread to California, North Dakota, Florida and Texas.

It was a young

person’s pandemic. In 1918-1919,

ninety-nine percent of Spanish Flu deaths were people under the age of 65. In

people between the ages of twenty and 40 years old, the rate was fifty

percent. It differed from previous

flu outbreaks in that its symptoms were so severe. Most people died of bacterial pneumonia, a secondary

infection. It also killed

directly, causing massive hemorrhages and edema of the lungs. Nurses noted fevers as high as 105

degrees and unusually severe bloody noses. Often the affected person turned

blue, and spit bloody mucus. It

was not usual for a person to die with a day or two of contracting the disease.

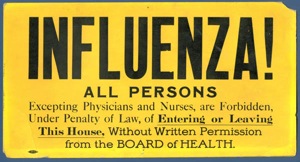

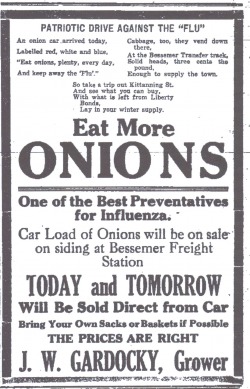

People did not know

how to stop the disease. One

common solution was to require that everybody wear a face mask. Posters appeared

asking people to cover their mouths and noses when the sneezed or coughed.

Another prevention method was to encourage men to stop spitting. Drinking alcohol was believed too prevent the flu that

became popular, so popular that it caused liquor shortages. Closing places where people gathered

like churches and theaters was common.

There were so many

cases that accurate records could not be kept. There was also a shortage of doctors and nurses, and those

who were available often came down with the flu themselves. Undertakers ran out of caskets, and

there was a shortage of gravediggers. Schools, theaters and businesses closed.

Telegraph and telephone service stopped because the operators were sick. Garbage went uncollected and mail was not

delivered. Since there was no

known cause or treatment, people tried other remedies like carrying a potato in

a pocket, or carrying a bag of camphor. Wearing a special amulet around the

neck. By November of 1918, the

number of new cases started to decline.

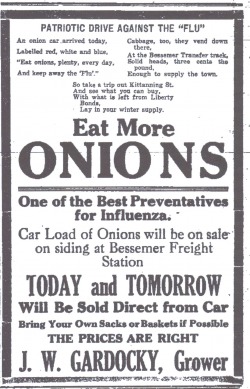

|

| People were willing to try anything to prevent the flu, and there were business people willing to capitalize on that. |

The flu disappeared

almost a quickly as it appeared.

People wanted to forget about it.

Most people didn’t realize how dangerous it was. When the Spanish flu pandemic began, it

was believed that bacteria caused the disease. Late in 1918, scientists and doctors realized that the cause

was a virus. Although the existence of viruses had been known for about 20

years, was not until 1933 that the type A flu virus was isolated, and not until

1944 that a vaccine for type A flu was available.

Although there have

been several flu pandemics since 1919, none have been as severe. The flu

pandemic of 1958-1959, (the Asian Flu), killed two million people worldwide and 70,000 in the

United States. Another pandemic in

1968-1969 (Hong Kong Flu) killed one million people worldwide and 33,000 in the United States.

In the swine flu pandemic of 2009-2010 (Swine Flu), 12,000 Americans died. Influenza is still a dangerous disease, but now there are effective vaccines and treatments for it, and modern flu pandemic have never been as lethal as the one in 1918.