|

| Woodcut by Jaques Hnivdovsky. Easter celebrations in Galicia. Baking the paska, cutting the pussy willow, Passion Thursday, blessing of the Easter baskets, the Hahilky dances, and ending with wet Monday. |

Easter was the most important holiday in Ukraine, when my

great Aunt, Katherine Rychly lived there, 100 years ago, in the village of Bila, just outside the city of Ternopil'. They called it

Velykden, which means big holiday.

It is important today, both in Ukraine and wherever Ukrainians live in

the world.

|

| Old Easter card |

Easter was a week long holiday, beginning on Holy Thursday

and ending on the Tuesday after Easter. Spring had arrived in Galicia an eastern province of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, and everybody was

excited about the warm sunshine and new growth. My great Aunt Katherine Rychly said that everybody in the family got new clothing

for Easter, blouses were made by a seamstress in the village, for all

the women. Their Easter clothing included a white apron, an important part of

their outfit. All the girls had their hair done, braided and decorated with

ribbons. On

Easter Day, the Church bells rang all day long and Everyone in the village went to Church for services, then home for a big holiday meal. After dinner, the family returned to

the church for Hahilky, songs and dances, performed by the girls of the village, on the grass outside.

Katherine does not mention in her memoir that the holiday continued

all week. Easter Monday was also

called “wet Monday” because the boys and girls spent the day dousing each other

with buckets of water. This

practice takes place in Poland as well. Provody ended Easter week in Galicia with visits to

the cemetery. Finally, after almost ten days of celebration, the villagers

returned to their every day lives.

It is no wonder that Easter was called Velykden—the great day.

Great Lent--The forty days leading up to Easter and " Pussy Willow Sunday"

The Easter season began with Lent. It began on Ash Wednesday and lasted 40 days. No meat was eaten and no dancing was

allowed. In Ukraine, Palm Sunday, the Sunday

before Easter was called Willow

Sunday. Pussy willow branches were used in place of palms, which

didn’t grow in Ukraine. The willow is an important tree to Ukrainians, and it was one of the first plants to show growth in the spring. The week

before Easter was sometimes called Willow Week. On Willow Sunday, the branches were blessed by the priest,

and the villagers tapped each other on the shoulder and repeated the wish: “Be as tall as the willow, as healthy

as the water, as rich as the earth.” Some farmers used the willow branches to drive their cattle to pasture

for the first time in spring, and then stuck the branch in the ground for

luck. After church, families took the pussy

willow branches home to decorate their houses, placing them behind the icons and the

cross.

|

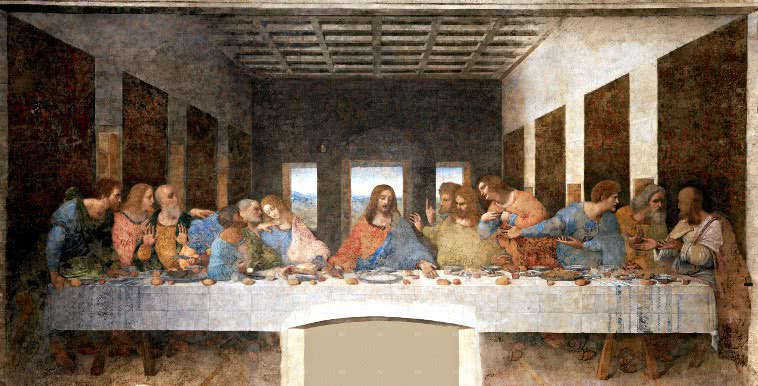

| "Maundy Thursday", painting by Mykola Pymenenko. Churchgoers left the services with lit candles on "Passion Thursday." |

The next four days were very busy. All preparations had to be

completed by Maundy Thursday, because no work could be done between Thursday

and Easter Tuesday. The house was cleaned and whitewashed. Easter foods were prepared, the Easter

breads, the Paska and the babki were baked and Easter eggs were made. Two types of Easter eggs were

decorated—the pysanky, elaborately painted raw eggs, which were often given as

gifts, and used in the Easter basket, and the krashanky, hard boiled eggs,

dyed various colors using vegetable materials. The most popular color was red, obtained by boiling the eggs

along with onion skins, until they took on a reddish brown color. Krashanky were

included in the Easter basket and eaten with the Easter meal.

The next four days were strict fast days, no meat or dairy could be eaten. The first service of the Easter observance was conducted on

Maundy or Passion Thursday. Large passion candles were lit during the service, and the people

carried the lit candles home.

On Good Friday, a “Tomb” was set up in the Church. A visit to the “Tomb” was made on

Saturday, before the Easter baskets were blessed.

The Blessing of the Easter Baskets

|

| Painting by Olena Kulchytska, "Christ Has Risen" , 1930 |

Every family put together an Easter basket, which contained very specific items. The Easter Babka was the most important, and pysanky and krashanky (at least one red one) were always included. the willow basket was lined with either an embroidered or white linen napkin. It contained a sausage, a piece of Easter ham, an Easter Babka, salt, butter, cheese and horseradish, which was called Hrin, and a beeswax candle. An embroidered towel covered the food in the basket and pussy willow branchhes decorated the handle. The baskets were brought to the church for blessing on the day before Easter. The people lined up, with their baskets in front of them. The priest walked "down the line" blessing baskets as he walked. The villagers were required to pay the priest for blessing their Easter basket with Easter bread if they didn't have cash. He received so much bread that day that he used it to feed his farm animals. This practice upset the villagers, children were hungry and the Priest used the special Easter bread to feed his animals!

Easter Day--Velykden

Bonfires were set and burned on the Saturday night before

Easter. In some areas,

the Easter basket was brought to the midnight service on Saturday. A vigil was sometimes held outside the

church, sometimes inside. In some churches, the

doors were opened as the sun rose greeting the worshipers with light.

On Easter morning, the faithful greeted each other with the saying

“Christ is risen!” They were

answered with “He is risen indeed.”

They would embrace and kiss three times. The family returned home with their Easter basket full of

food and enjoyed the Easter meal.

|

| "Easter Vigil" painting by Mykola Pymenenko |

Vesnianky-Hahilky

The Vesnianky-Hahilky celebration took place in front of the

church during the afternoon of Easter Sunday. The origin of these songs and dances were very ancient: before

the Ukrainians became Christian in the 10th century, the purpose of

these celebrations was to chase away winter and welcome spring. The people asked the forces of nature

to give them a bountiful harvest and a happy life. The Vesnianky-Hahilky specifically Galician customs, and

were not performed in other areas of Ukraine. Only young unmarried women took part dancing round dances,

without partners. As time passed,

the ancient reasons for the dances were forgotten, and the Hahilky were performed for

entertainment. By the turn of the

last century, courtship became a reason for the hahilky; my grandmother told me

that a pretty young girl was often noticed on Easter Sunday, and engaged soon

after. During the

years of the Soviet Union, the hahilky disappeared in Ukraine, but are now

performed in Ukrainian communities in Europe and North and South America.

, , |

| "Hahilky" painting by Ivan Trush, 1905 |

The Rest of Easter Week

Wet Monday followed Easter Sunday. The boys sprinkled—or doused the girls with water. The

Rychly family ate vareneky (pirogi) on Easter Monday, using the leftover cheese from the Easter dinner. The Friday and Saturday after Easter was called Provodny in

Galicia, a day to remember departed family members. The family went to the cemetery with a picnic, and left some

food and Easter eggs at the graves.

The Easter season ended with “Green Sunday” or Pentecost, 40

days after Easter.

|

| Paskas, babkas and the Easter Basket. |

|

| Krashanky, hard boiled eggs, colored with onion skins. |

Martha Stuart's Recipe for Ukrainian Easter Paska Click on the link for the recipe

Special instructions for making the Paska--in addition to the recipe above

- When preparing paska dough and during the kneading, think only good thoughts, shoo away all evil ones.

- Don't let any of your neighbors or any strangers come in the house when you are preparing the paska. It will not rise as it should. Don't make any sudden noises while the paska is rising or while it is in the over baking. Don't sit down while the paska is baking or it will become flat.

- If you carefully follow all of the instructions, the paska will be light, airy and tasty. If not, it will come out hard and dense.

Source: The Ukrainian Museum, New York

Other sources:

Ukrainian Easter at BRAMA, brama.com/art/easter.html

Encyclopedia of Ukraine, encyclopedia of ukraine.com

Lawryk, Julia, Kateryna, Autobiography by Katherine Pylatuik Lymar as told to her Daughter, Julie in 1988.

Ukrainian Museum of Art, Kiev, Ukraine

Lviv Museum of Ukrainian Art, Lviv, Ukraine

,

,