|

| Source: luszpinski.net |

When I was growing up, I assumed that finding my family history in Eastern Europe was impossible. I believed that because of the wars, many records were destroyed and when Ukraine became a part of the Soviet Union in 1939, all remaining records were either destroyed or were impossible to access. Believing this made discovering my family history impossible.

I did have some basic information, my maternal grandmother gave me the names of her grandparents and aunts and uncles, and some information about her childhood. Her sister wrote a wonderful memoir about growing up in a Ukrainian village. Since I had that, I was able to piece together a basic history of the Rychly family in Ukraine. My maternal grandmother, Pauline Rychly Koshuba Haydak gave me some information about my maternal grandfather's family, the Koshubas.

I had very little information about my father's family, the Klak and Nyznyk families but when my father had to find information in order to get a US passport, he found the names of both his paternal and maternal grandparents. Now I had something to look for.

The Nyznyk family of Pomorzany or Pomorany, is the family about which I know the least. I have researched my grandfather, John Nyznyk in New York, but the search information about him goes cold after 1940. I decided to go back in time and find out about two of my grandparent's families, the Nyznyk and Romanowicz families. I was lucky that the Family History Center has the Metrical Records from the Greek Catholic Church of Pomorzany from 1837 to 1862 on film. I have found have found a lot of ancestors on these films , but I still can't fit the puzzle pieces together yet. What I can do is tell about life in this village during the twenty five years between 1837 and 1862.

The Metrical Records are easy to read, since they are written in Latin and arranged in columns. In 1793, after the First Partition of Poland, the Austrian government required that vital statistics be kept in all areas acquired in the partition. Local Roman and Greek Catholic churches served as recorders of all vital statistics and that two copies of every record be made, one to stay in the church, the other to be kept in another place, in this instance in the city of Lviv. All birth, death and marriage records were kept by the Greek Catholic and Roman Catholic Churches at first, eventually Jewish synagogues and other Christian denominations were also able to record and kept vital statistics. The LDS Church has filmed vital records in many Ukrainian villages and towns which are kept in Salt Lake City and are accessible at Family History Centers all over the world.

|

| The birth record in Latin and English |

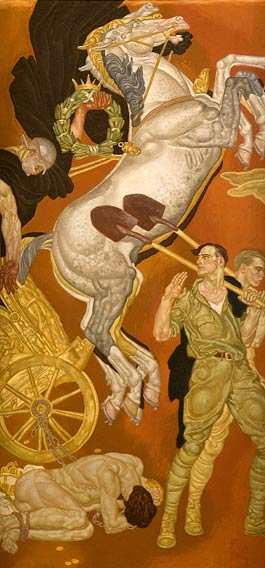

Every record includes names, dates and places where the life event occurred. Sometimes parent's names are included and occupations are noted as well. Since local clergymen wrote all the information with pen and ink, they give a look into the past when beautiful penmanship was necessary and appreciated. First names were recorded in Latin and surnames were listed in Polish. "Conditio" which means occupation in Latin is noted on all records. Agricola was the Latin word for farmer, and the most common occupation. Nyznyk and Romanowicz family members were listed as pelleo, or persons who worked with skins and hides. Other common occupations were sutor or sudor, shoemaker, and fabrile, a person who works with metal. In the 1850's laborers began to appear, and mendicane, or beggar was also listed.

Marriage records contained the most information; the names

of the persons to be married were listed along with their ages and occupation for the groom. His parent's names and occupations followed, sometimes the grandparents were also listed with their occupations. The bride's information was listed in a separate column. The information was similar, but women did not have occupations. Both the bride's and

groom's house numbers were listed.

|

| A example of a marriage record. Source Stumbleblock.wordpress |

When a birth was recorded, the name of the father was listed first, the mother's first name was listed, followed by "daughter of" and her father's first and last name and occupation. The date of birth was listed, followed by the dates of baptism and confirmation. The house number listed where the birth occurred, which was not always in the home of the parents. Married couples went to live with the husband's parents, so the first child was usually born in their house. A different house number might be listed for the birth of a second child, because the couple now had their own house. In an illegitimate birth, only the mother's name was mentioned. Second marriages were also recorded, but not as much information was included. A death record included the person's age, date of death and burial, and cause of death.

|

| Example of a birth record from 1907, column headings are in Latin and Ukrainian. |

In the 1830's, most causes of death were listed as "ordinario" or ordinary; later, specific diseases were listed. In a death entry, a man's name stood alone, but a woman was listed either as "daughter of" followed by her father's name if she was not married, or "wife or/widow of" followed by her husband's name. The house number was always included. From information in the Metrical Records, many more children died than

adults. Very few people lived to a great age, most died

in their fifties or sixties. Common causes of death were convulsions,

epilepsy, consumption (tuberculosis), pleurisy, fibrio gastris and

cholera. In 1850, eleven people died of fibrio gastris between the

beginning of September and the end of October, mostly adults. 1855 saw a

cholera epidemic between July and September. 59 villagers died, mostly

children at first, adults later. In the Gudziak (cousin of the Nyznyk

and Romanowicz families) home, four family members died within days of

each other, first two daughters, then the father and grandmother.

|

| Death record from 1838. Source: Kowalfamily.wordpress |

Pomorzany grew; in 1837, there were a little over 300 houses, by 1859 there were over 700 houses in the town. Most people stayed in the town, and I saw the same surnames repeated over the 25 years. Cousins often married cousins. Sons followed their father's occupation. Most people married people with the same occupation. The Nyznik and Romanowicz families worked with leather, and their sons and daughters married children of other leather workers. When a young married couple could afford their own house, they often moved, and this shows up in a new house number. One change in the records during the 25 years I studied was in 1855 when the column headings were in both Latin and Ukrainian. The next year, the Ukrainian heading disappeared. In the birth record example above from 1907, the heading were in both languages. In the earliest records, the family surname was spelled Nisnik. In 1856, the spelling changed and it was spelled Niznik. There were trends in first names: John was always popular for boys, Maria for girls. Anastasia and Tecla were also popular for girls. Rarer first names were Erasmus and Procopious and Parascevia and Michalina.

There is more to be learned about Pomorzany, and there are still hundreds of records to be reviewed.

|

| Wooden Church in Pomorzany. Source: Wikimedia.org |